In the last episode of "Crimson Field" there is a passing reference of a nurse being executed for treason. At the end of this series, it mentions it is dedicated to the memory of

EDITH CAVELL. Of course I had to look up who she was.

Edith Louisa Cavell (1865-1915) was a British nurse. She is celebrated for saving the lives of soldiers from both sides without discrimination and in helping some 200 Allied soldiers escape from German-occupied Belgium during the First World War, for which she was arrested. Her execution received worldwide condemnation and extensive press coverage. Edith, who was 49 at the time of her execution, was already notable as a pioneer of modern nursing in Belgium.

![]() |

| Edith (Center) with nurses she trained |

There were posters all over Brussels warning that, "Any male or female who hides an English or French soldier in his house shall be severely punished." In spite of this warning, there were soon successful efforts to hide soldiers who were wounded or separated from their units, then given refuge and helped to escape to safety. In Edith's hospital, wounded Allied soldiers were tended and then helped to escape.

Soon Edith was persuaded to make room for some of the unfortunates who were not wounded but merely fleeing the Germans. They too were helped to get to places where they could rejoin Allied forces. The Germans became more watchful of the comings and goings at the hospital and Edith was warned by friends that she was suspected of hiding soldiers and helping them escape. But her strong feelings of compassion and patriotism overruled the warnings and she continued to do what she thought was her duty.

On 15 August 1915, as was almost inevitable, she was arrested by the German police and charged with assisting the enemy. The Germans suspected that not only were she and others helping Allied soldiers but that the same communication lines were used to divulge German military plans - a serious charge indeed.

Edith was held incommunicado for ten weeks. Brand Whitlock, the American minister to Belgium, was refused permission to see her.

Even her appointed defense lawyer, Sadi Kirchen (a Brussels attorney), was not allowed to see her until 7 October, the day her trial began. Thirty-four others were accused of the same crime and were tried as a group. Several of the accused were friends of Edith's who had worked with her in helping the Allied soldiers.

The trial lasted only two days. Each person was accused of aiding the enemy and was told that, if found guilty, would be sentenced to death for treason. Edith's lawyer was eloquent in her defense, saying that she had acted out of compassion for others. Edith openly admitted that she had helped as many as 200 men to escape, who she knew they could then be able to fight the Germans again, and that some of them had written letters of thanks for her help. This was enough to cause her to be judged guilty and the sentence to be executed.

The final judgment was postponed for three days and during that time desperate attempts were made to save her. The American legation petitioned the German authorities in Brussels. A group composed of M. de Leval, the Belgian councilor to the American Legation; Hugh Gibson, secretary to the American Legation; and the Marquis de Villalobar, the Spanish minister to Belgium, made a hurried visit to the political governor of Brussels, Baron von der Lancken. He listened to their pleas but said that he could not reverse the court's decision. Only the military governor, Von Sauberzweig, had such authority. But even he, after being reached by phone, said that the sentence had to be carried out. In despair, the three men left they could do no more.

![]()

![]() |

|

On 11 October the prison chaplain, the Rev. Gahan, visited Edith and found her resigned to her fate. She told him. "I want my friends to know that I willingly give my life for my country. I have no fear nor shirking. I have seen death so often that it is not strange or fearful to me." Even the German chaplain praised her for being "brave and bright to the last." On the morning of 12 October Edith Cavell and Philippe Baucq were taken to the Tir National, the Brussels firing range. At 7 a.m. both lay dead in the morning sun.

Her death provoked international condemnation, with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle writing: "Everybody must feel disgusted at the barbarous actions of the German soldiery in murdering this great and glorious specimen of womanhood."

Edith, who was 49 at the time of her execution, was already notable as a pioneer of modern nursing in Belgium. But there is more to the story!

New evidence reveals Edith Cavell's resistance network was sending secret intelligence to the British.

Recent exploration of the military archives in Belgiumshow Edith Cavell’s organization was a two-pronged affair" and that espionage was the other part of its clandestine mission.

The Belgian archives contain reports and first-hand testimonies collected at the end of the First World War. In “Secrets and Spies: The Untold Story of Edith Cavell”, historian Dr Jim Beach said military espionage was in its infancy at the beginning of the First World War, and Cavell's associates were amateurs.

While we may never know how much Edith knew of the espionage carried out by her network, she was known to use secret messages, and we know that key members of her network were in touch with Allied intelligence agencies.

According to Julian Hendy, producer of the documentary: "Cavell was certainly not a naive woman - her shrewd testimony before her German interrogators proved that. As so many leading members of the network were involved in espionage, it would have been truly extraordinary for her to have been completely unaware of the intelligence-gathering.

"The story we have always been led to believe – of a simple nurse just doing her duty helping soldiers – turns out to have been a lot more complicated, nuanced, and dangerous than we had ever previously thought."

She is well known for her statement that "patriotism is not enough". Her strong Anglican beliefs propelled her to help all those who needed it, both German and Allied soldiers.

She was quoted as saying, "I can’t stop while there are lives to be saved." The Church of England commemorates her in their Calendar of Saints on 12 October.

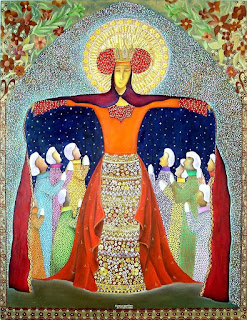

![]() |

| Brian Whelan for Exhibition of 100 Ann. of her death (2015) |

![]() |

| Monument in London |

![]() |

| Monument in Norwich |