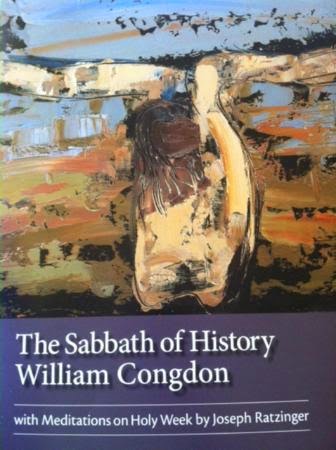

Our artist for Holy Week has given us the most number of crucifixions. WILLIAM CONGDON, born in Providence, Rhode Island in 1912 was an American painter who gained notoriety as an artist in New York City in the 1940s, but lived most of his life in Europe, dying in Milan in 1998.

Our artist for Holy Week has given us the most number of crucifixions. WILLIAM CONGDON, born in Providence, Rhode Island in 1912 was an American painter who gained notoriety as an artist in New York City in the 1940s, but lived most of his life in Europe, dying in Milan in 1998.He lived a profoundly personal and Christian life after his conversion to Catholicism in 1959. After living for a year in Venice, he took up permanent residence in Assisi where he lived for the next 19 years. In 1979, though not a monk, he moved permanently to a studio apartment attached to a new Benedictine community in the monastery of Saints Peter and Paul outside of a small village near Milan. For the last 19 years of his life the lowlands of the Milanese countryside were the major inspiration of his art. Many felt this move was "suicide" to his art!

His own words from his journals speak more than all the critics about the man and his work.

"I know I won't sleep any more .. I am slowly sinking into the depths of original nothingness until at a certain point I recognize that I am smiling and smiling with the smile of another of the Face of the Other who is these pastels who is their naked rigorousness of nothingness that from the Cross explodes in the shout of all who is this miracle that creates the universe, that re-creates me and from the depths of the anguish of original nothingness I feel myself float up and up again-- and I sleep." (Manuscript, April 18, 1989.)

During the late 1950s Congdon's life was often in a state of agony. Having early in life been deprived of a close relationship to his family and his roots in New England, and his search around the globe for a surrogate had failed. He writes about the "destructive projection of his ego" and also of feelings of self-doubt and sin in his disordered life. In 1951 in Assisi he had met Don Giovanni Rossi, the founder of the association Pro Civitate Christiana, who had welcomed him with affection and who held out hope.

In the Sahara Desert in 1955 a French waiter quite fortuitously gave Congdon a copy of the Confessions of St. Augustine, a book that took on increasing significance for the artist in his solitude. Perhaps it was St. Augustine's conviction that he who searches for God has already found God within himself, which helped the artist in his determination to alter the direction of his life.

He returned to Assisi, converted to Catholicism, and was baptized in August 1959. He was received by the lay movement Pro Civitate Christiana and moved into an old, small house in Assisi, where he began his long cycle of religious paintings. He now no longer painted in isolation, but felt able to relate his work to a larger community.

"I felt the weight of Christ on my pictures, on my very creative freedom. In those years few pictures came to birth, and they would not have come to birth -I lament-if I always had to think of Christ when I painted. When I heard that the Blessed Angelico painted with a brush in one hand and the Gospel in the other, it struck me as the most absurd nonsense. One of the greatest difficulties for the artist who offers himself to conversion is letting Christ settle in. The autonomy of art is an inviolable, untouchable mystery that, like the Spirit, "blows where and when it wills.""A collision of two mysteries," a friend said to me. One mystery the artist had already within himself. God has given it to him, and the artist will only permit God, with difficulty, to take it from him in order to have the artist accept another mystery that he neither sees nor touches, even if this latter mystery promises to recover and to regenerate the first mystery which was lost."

|

"After my baptism in the Catholic Church at Assisi in 1959, the figure again became explicit in the form and content of the Cross. However, it is perhaps inevitable that the encounter with Christ and the discovery that his drama of the Cross is also my own- I mean for our salvation - should lead me to the Crucifix through a return to the figure."